[This is a Guest Diary by Rachel Downs, an ISC intern as part of the SANS.edu Bachelor’s Degree in Applied Cybersecurity (BACS) program [1].

Scanning on port 502

I’ve been running my DShield honeypot for around 3 months, and recently opened TCP port 502. I was looking for activity on this port as it could reveal attacks targeted towards industrial control systems which use port 502 for Modbus TCP, a client/server communications protocol. As with many of my other observations, what started out as an idea to research one thing soon turned into something else, and ended up as a deep dive into security research groups and the discovery of a lack of transparency about their actions and intent.

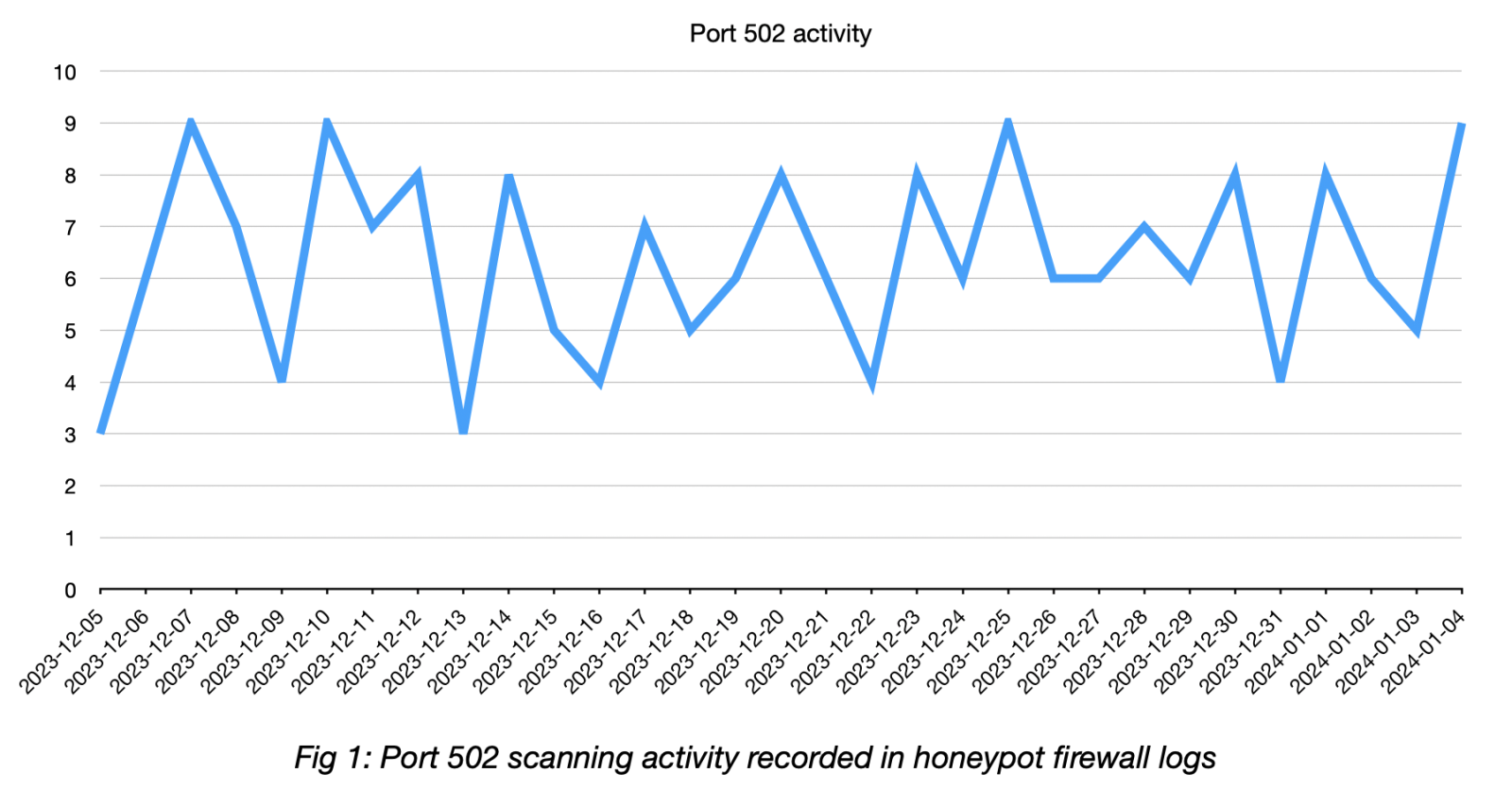

I analysed 31 days of firewall logs between 2023-12-05 and 2024-01-04. Over this period, there were 197 instances of scanning activity on port 502 from 179 unique IP addresses.

Almost 90% of scanning came from security research groups

Through AbuseIPDB [2] and GreyNoise [3], I assigned location, ISP and hostname data (where available) to each IP address. GreyNoise assigns actors to IP addresses and categorises these as benign, unknown or malicious. Actors are classified as benign when they are a legitimate company, search engine, security research organisation, university or individual, and GreyNoise has determined the actor is not malicious in nature. Actors are classified as malicious if harmful behaviours have been directly observed by GreyNoise, and if an actor is not classified as benign or malicious it is marked as unknown [4].

I used this classification, additional data from AbuseIPDB, and the websites of self-declared security research groups to categorise the scanning activity observed in my honeypot firewall logs.

89% of the total scanning activity was attributed to security research groups, 3% was attributed to known malicious actors and 8% was unknown.

Who are these researchers, and why are they scanning?

Almost half of the activity classified as security research came from two groups: Stretchoid and Censys. Other frequently observed groups included Palo Alto Networks, Shadowserver Foundation, InterneTTL, Cyble and the Academy for Internet Research. The remaining groups were only observed scanning port 502 once or twice each, including Shodan.

The motivations of these different research groups varies, and for some their purpose is unclear or unstated. Some are academic research projects, some are commercial organisations collecting data to feed into their products and services, and others are less clear.

Stretchoid was the most active actor identified, accounting for 25% of security research activity. There is very little information available about them, aside from an opt-out page. The page states “Stretchoid is a platform that helps identify an organisation’s online services. Sometimes this activity is incorrectly identified by security systems, such as firewalls, as malicious. Our activity is completely harmless” [5]. However, there is a lack of transparency around the organisation responsible for Stretchoid and as such, online discussions about them urge caution around submitting data through the opt-out form [6].

Censys conducts internet-wide scanning to collect data for its security products and datasets [7].

Palo Alto Networks were able to be identified using the ISP name, however they did not enable reverse DNS lookup for hostnames to identify the scanner being used. These IP addresses are marked as benign in GreyNoise and attributed to Palo Alto’s Cortex Xpanse product.

Shadowserver Foundation describe themselves as “a nonprofit security organisation working altruistically behind the scenes to make the internet more secure for everyone” [8].

InterneTTL’s website was not active at the time of this report, however GreyNoise points to it being a security research organisation that regularly mass-scans the internet [9].

Cyble describes its ODIN product as “one of the most powerful search engines for internet scanned assets”. It carries out host searches, asset discovery, port scanning, service identification, vulnerability detection and certificate analysis [10].

The Academy for Internet Research’s website states they are “a group of security researchers that wish to make the internet free, safe and accessible to all” [11].

bufferover.run is identified by GreyNoise as a commercial organisation that performs domain name lookups for TLS certificates in IPv4 space. GreyNoise has marked this actor as benign but it is unclear why they are carrying out port scanning activity [12].

Crowdstrike was seen twice via scans from Crowdstrike Falcon Surface (Reposify), which they describe as “the world’s leading AI-native platform for unified attack surface management” [13].

SecurityTrails is a Recorded Future company offering APIs and data services for security teams [14].

Shodan scanners were seen twice. These are used to capture data for Shodan’s search engine for internet-connected devices [15].

Alpha Strike Labs is a German security research company producing open source intelligence about attack surfaces using global internet scans. They claim to maintain more than 2000 IPv4 addresses for scanning [16].

BinaryEdge “scan the entire public internet, create real-time threat intelligence streams and reports the show the exposure of what is connected to the internet” [17].

CriminalIP is an internet-exposed device search engine run by AI Spera [18].

Internet Census Group is led by BitSight Technologies Inc and states data is collected to “analyse trends and benchmark security performance across a broad range of industries” [19].

Internet Measurement is operated by driftnet.io and is used to “discover and measure services that network owners and operators have publicly exposed”. They offer free access to an external view of your network from the data they have gathered [20].

Onyphe describes itself as a “cyber defence search engine” [21]. They provide an FAQ about their scanning on their website.

The Technical University of Denmark’s research project aims to identify “digital ghost ships” [22], devices which appear to be abandoned and un-maintained.

A lack of transparency

The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), when launching its own internet scanning capability, provided some transparency and scanning principles [23] that they committed to following, and encouraged other security researchers to do the same:

Publicly explain the purpose and scope of the scanning system

Mark activity so that it can be traced back to the scanning system being used

Audit scanning activity so abuse reports can be easily and confidently assessed

Minimise scanning activity to reduce impact on target resources

Ensure opt-out requests are simple to send and processed quickly

Adherence to these principles varied between the research groups observed, but was generally quite poor among the more prolific scanners in this observation. It was not possible to observe whether research groups were auditing scanning activity, so this is not rated in the table below.

Fig 4: An analysis of security research groups’ adherence to NCSC’s ethical scanning principles

Fig 5: A guide to the ratings used in Fig 4

This lack of transparency makes it difficult to determine whether this activity is truly benign.

Good practice is demonstrated by Onyphe, who provide information about their scanning and their “10 commandments for ethical internet scanning” on their website. Along with the Technical University of Denmark, they also provide a web server on each of their probes which explains the purpose, intent and the ability to opt out.

Why does this matter?

The volume of scanning activity related to security research is significant, and has an impact on honeypot data. This has been discussed in a previous ISC blog post by Johannes Ullrich, “The Impact of Researchers on Our Data” [24]. Quick and accurate identification and filtering of research activity enables honeypot operators to more rapidly identify malicious activity, or activity that requires further investigation.

Equally, the presence of honeypot data in security research scans impacts the conclusions that will be drawn by researchers about the presence of open ports and vulnerable systems, and the estimated scale of these issues.

Although researchers themselves may not be using the data collected for malicious purposes, they may lose control of how the data is used once it is shared or sold elsewhere. For example, Shodan scanning activity is classed as security research, however the resulting data can be used by attackers to find vulnerable targets.

Some of the organisations involved in this scanning are profiting from the data collected from your systems, utilising your resources to do this. Ethical researchers should allow you to opt-out of this data collection.

Security research is a broad term, and the intent behind scanning activity is not always clear. This makes security research something of a grey area, and means transparency is key in order for informed decisions to be made.

What should I do?

As a honeypot operator, or someone responsible for monitoring internet-facing systems, you may decide to reduce scanning noise by blocking security research traffic. This is made difficult when researchers don’t publish the IP addresses they use, or don’t provide the ability to opt-out. To help with this, the ISC provides a feed of IP addresses used by researchers through their API [25].

All activity relating to Stretchoid, the most active research group in this observation, originated from DigitalOcean. Some users recommend blocking DigitalOcean’s IP ranges (unless this is required for your organisation) as an alternative to opting out.

A number of GitHub projects also exist to track the IP ranges of Stretchoid and other security research groups, such as szepevictor’s stretchoid.ipset [26].

Research groups could do more to build trust and help security teams separate benign activity from malicious. If you carry out internet scanning activities, it’s a good idea to follow the NCSC guidance discussed in this blog post to maintain transparency and allow others to make informed decisions about allowing or blocking your scans.

Enabling reverse DNS and using hostnames that identify your organisation or scanner is a good way to make your scanning activity identifiable, and an informative web page with a clear explanation of the purpose of data collection, including the ability to opt out, helps demonstrate your positive intentions.

[1] https://www.sans.edu/cyber-security-programs/bachelors-degree/

[2] https://www.abuseipdb.com

[3] https://www.greynoise.io

[4] https://docs.greynoise.io/docs/understanding-greynoise-classifications

[5] https://stretchoid.com/

[6] https://www.reddit.com/r/cybersecurity/comments/10w2eab/stretchoid_phishing_and_recon_campaign/

[7] https://about.censys.io/

[8] https://www.shadowserver.org/

[9] https://viz.greynoise.io/tag/internettl?days=1

[10] https://getodin.com/

[11] https://academyforinternetresearch.org/

[12] https://viz.greynoise.io/tag/bufferover-run?days=1

[13] https://www.crowdstrike.com/products/exposure-management/falcon-surface/

[14] https://securitytrails.com/

[15] https://www.shodan.io/

[16] https://www.alphastrike.io/en/how-it-works/

[17] https://www.binaryedge.io/

[18] https://www.criminalip.io/

[19] https://www.internet-census.org/home.html

[20] https://internet-measurement.com/

[21] https://www.onyphe.io/about

[22] https://www.dtu.dk/english/newsarchive/2023/01/setting-out-to-sink-the-internets-digital-ghost-ships

[23] https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/blog-post/scanning-the-internet-for-fun-and-profit

[24] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/The+Impact+of+Researchers+on+Our+Data/26182

[25] https://isc.sans.edu/api/threatcategory/research (append “?json” or “?tab” to view in JSON or tab delimited format)

[26] https://github.com/szepeviktor/debian-server-tools/blob/master/security/myattackers-ipsets/ipset/stretchoid.ipset

—

Jesse La Grew

Handler

(c) SANS Internet Storm Center. https://isc.sans.edu Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.